Read several short writings available on the Library of Congress website, based on factual information from the events they address: http://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/9805/religion.html

Included among them are these:

Religion and the Constitution

When the Constitution was submitted to the American public, “many pious people” complained that the document had slighted God, for it contained “no recognition of his mercies to us … or even of his existence.” The Constitution was reticent about religion for two reasons: many delegates were committed federalists who believed that the power to legislate on religion, if it existed at all, lay within the domain of the state, not the national, governments. Second, the delegates believed that it would be a tactical mistake to insert such a politically controversial issue as religion in the Constitution. The only “religious clause” in the document — the proscription of religious tests as qualifications for federal office in Article Six — was, in fact, intended to defuse controversy by disarming potential critics who might claim religious discrimination in eligibility for public office.

Religion and the Bill of Rights

Although there were proposals for making the ratification of the Constitution contingent on the prior adoption of a bill of rights, supporters of a bill of rights acquiesced with the understanding that the first Congress under the new government would attempt to add to it a bill of rights.

James Madison took the lead in steering a bill of rights through the First Federal Congress, which convened in the spring of 1789. The Virginia Ratifying Convention and Madison’s constituents, among whom there were large numbers of Baptists who wanted freedom of religion secured, expected him to push for a bill of rights. There was considerable opposition in Congress to a bill of rights of any sort on the grounds that it was “unnecessary and dangerous.” The persistence of Madison and his allies nevertheless carried the day and on Sept. 28, 1789, both houses of Congress voted to send 12 amendments to the states. Those ratified by the requisite three fourths of the states became in December 1791 the first ten amendments to the Constitution.

Religion was addressed in the First Amendment in the following familiar words: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” In notes for his speech, June 8, 1789, introducing the bill of rights, Madison indicated that a “national” religion was what he wanted to prevent and it is clear that most Americans joined him in considering that the major goal was to forestall any possibility that the federal government could act as several Colonies had done by choosing one religion and making it an official “national” religion that enjoyed exclusive financial and legal support. The establishment clause of the First Amendment meant at least this: that no one religion would be officially preferred above its competitors. What ever else it may — or may not — have meant is obscured by a lack of documentary evidence and is still a matter of dispute.

Pastor’s note: There is no dispute of meaning of freedom of religion when you read the letters and view the body of work by those who wrote the words in question as to the roles of church and state and connection between. The dispute is not of fact, but how the opponent to the fact feels about the facts. And feelings do not change the facts. We have seen the misinterpretation of a letter regarding separation of church and state used as the means to prevent all things religion from sharing a room with all things federal, state and local government supported. It is, as it was when it was misinterpreted, a complete fabrication without foundation in truth. Although I could offer countless examples, I offer the following.

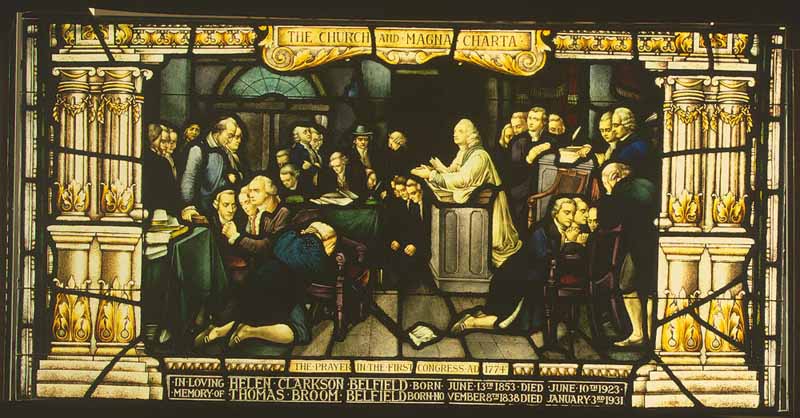

Read on regarding a tradition in our congress that continues to this day. Every session of the people’s house begins with devotion and prayer from a member of one of the country’s many denominations. When chaplains became part of Congress…

George Duffield, Congressional Chaplain

On October 1, 1777, after Jacob Duché, Congress’s first chaplain, defected to the British, Congress appointed joint chaplains: William White (1748-1836), Duché’s successor at Christ Church, Philadelphia, and George Duffield (1732-1790), pastor of the Third Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia. By appointing chaplains of different denominations, Congress expressed a revolutionary egalitarianism in religion and its desire to prevent any single denomination from monopolizing government patronage. This policy was followed by the first Congress under the Constitution which on April 15, 1789, adopted a joint resolution requiring that the practice be continued.

Washington’s Farewell Address

Washington’s Farewell Address is one of the most important documents in American history because the recommendations made in it by the first president, particularly in the field of foreign affairs, have exerted a strong and continuing influence on American statesmen and politicians. The Farewell Address, in which Washington informed the American people that he would not seek a third term and offered advice on the country’s future policies, was published in David Claypoole’s Philadelphia American Daily Advertiser on Sept. 19, 1796, and was immediately reprinted in newspapers and as a pamphlet throughout the United States. The Address was drafted in July 1796 by Alexander Hamilton (Washington also had at his disposal an earlier draft by James Madison) and was revised for publication by the president himself.

The “religion section” of the Farewell Address was for many years as familiar to the American people as Washington’s warning that the United States should avoid entangling alliances with foreign nations. The first president advised his fellow citizens that “Religion and morality” were the “great Pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of Men and citizens.” “National morality,” he added, could not exist “in exclusion of religious principle.” “Virtue or morality,” he concluded, as the products of religion, were “a necessary spring of popular government.”